AI is shaking not only the creative industry, but our entire culture.

Herein, I will skip the ethical issues tied to AI and focus only on the artistic side of the problem, commonly referred to as AI art.

What many worry about AI, is the end of true human creation in lieu of an automated solution.

Like many, when I see AI-generated images, I feel some sort of aversion: the results are over stylized, always recognizable, lackluster. But then I think that, after all, AI is nothing exactly new.

Sure, if we compare it to what we were used to only a few years ago, we are in the presence of advanced technology. But most of the conversations look at the problem from the same angle: the technology. We are basically incapable at this point of separating ourselves, or our thinking I should say, from the very technical culture that forged us.

The question is not how good or bad AI is, or how capable it is at replacing artists, but rather how we got to call ourselves artists in the first place.

What I see here is the crisis of language: If we change the meaning of a word, we change the concept.

We have now content creators (the act of writing an article or talking head in a video), films (motion graphics employed in commercial product advertisement), artists (anyone), or the word surrealism thrown at every quirky image.

So, the question we should ask ourselves is: when did we stop being photographers, designers, illustrators, animators, and become artists? There lies a pivotal change.

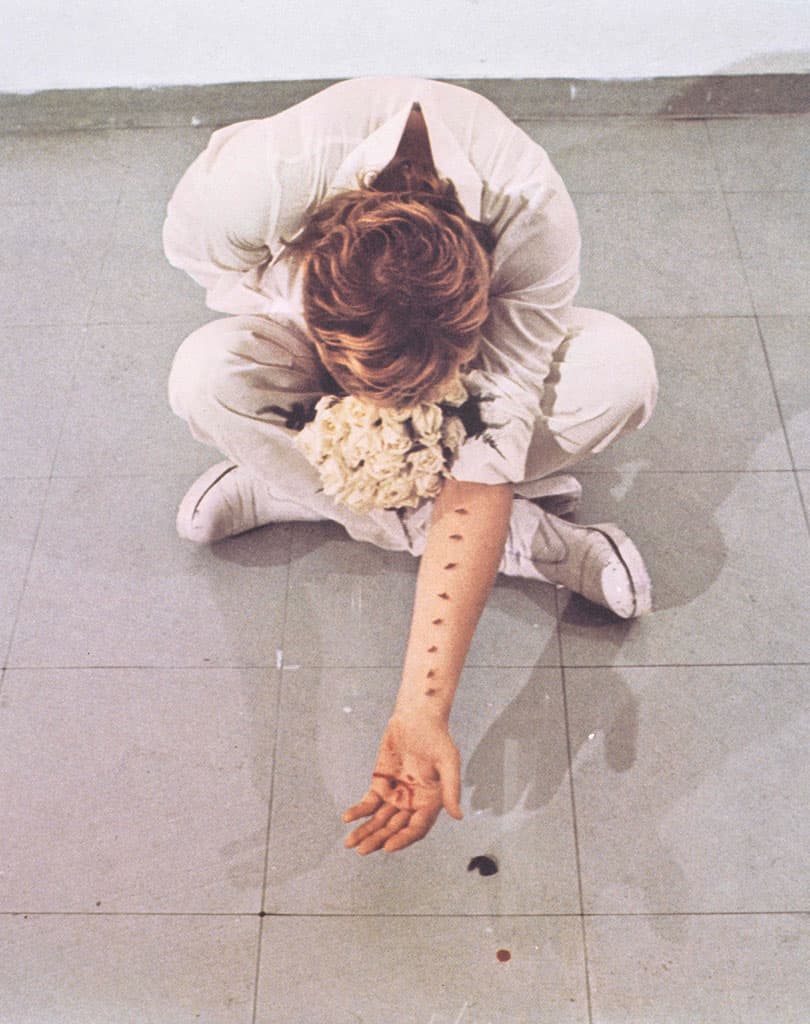

Being an artist used to mean that you would dedicate your whole life not only to a discipline, but to an ethic, a philosophy. It used to mean that you would challenge clichés, stereotypes. Lastly, it used to mean that you would be also ready to die for it (some still seem to fit that description, but let’s not misunderstand a workaholic with an artist).

I never see my job as an art form. Creative? Yes, but art? No. I think we’re more craftsmen than artists. At the very core, we help clients get their message through.

Of course, some would argue that beauty is in the eye of the beholder, that if I create something that I deem artistic, therefore it is. That is an oxymoron since if anything can be art, then nothing it is in that we’re devaluing the uniqueness of the thing itself being artistic. Which would mean that AI art is art too.

Furthermore, it poses an historical consciousness problem, in that it ignores all the progress art went through, its principles, its language, its internal conflicts, the challenges all the artists before us had to overcome in order to establish the new.

The naive principle that if the viewer considers something beautiful, therefore is art, has pervaded the layman mentality. Establishing what is art and what is not, it’s not an easy task, despite we would like it to be. But that doesn’t mean that it can be whatever I want it to be without imbuing my act of profound meaning, concept, intent, while ignoring the past (those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it — George Santayana).

Lastly, art is not something beautiful a priori. In fact, it can be ugly.

Serra: “I don’t think it is the function of art to be pleasing… Art is not democratic. It is not for the people.” 1

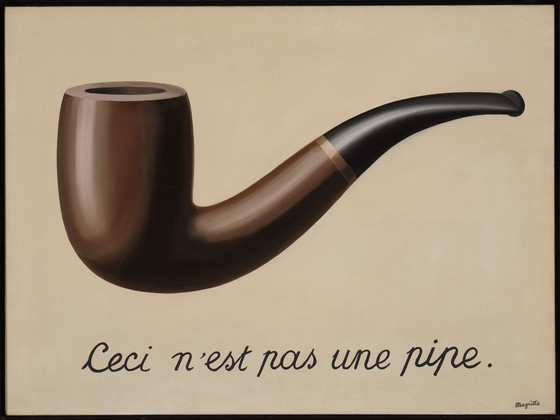

Art is not set in the form of illustration, sculpture, architecture, etc. Again, we mistake the technique (illustration) for art because we think in technical terms. Even a painting is not a work of art until there’s something else that goes beyond the representation of the thing depicted. It’s the profound misunderstanding of the signified and the signifier.

It is the artist who employs those techniques in order to convey a message.

Magritte (who, contrary to the common interpretation, wasn’t actually a surrealist painter but rather a conceptual artist), painted not because he was primarily a painter, but because that was the main means for him to express his ideas: “A painter is a good draftsman, and I see his picture. Well, that can’t help me any more than the carpenter who’s done a good job on his table.”

When I hear animators, designers, lamenting how AI art is nothing but a mockery, that AI is not true art, I would like to ask them: and in which way are you an artist?

But above all: who in the first place sold the idea that doing 3d renders (no matter how beautiful they are) makes you an artist? You’re still a 3d designer, or an illustrator, an animator, etc.

The confusion started with the industry itself, we started this, and now we’re unhappy to see the results of a twisted logic that turned against us. It’s not a coincidence that we mistake being technically skilled with being an artist: the more intricate, or complex the results are, the stronger the association with art. We can only judge from a technical standpoint. No wonder AI seems a worthy successor.

So, let’s take a step back. Let’s define our roles for what they are, without this romanticized idea of what we dream of. If we all call ourselves for what we actually do, there won’t be AI art anymore, but only AI “3d-like” renders, AI “illustration-like”, etc. It won’t be the definition of our profession at stake anymore, but just the task. And if that happens, it will be a little less difficult to explain that a machine can only replicate a task, but cannot replace a profession.

Only then, I’d be willing to consider whether to accept AI as a tool amongst the others I already use.

- No matter how ugly the Tilted Arc can be regarded as, the provocation is quite profound. How the urban environment can affect our feelings, or even behaviors? What impact the architecture has on our subconscious? . ↩︎

Leave a Reply